Quick Guide to Estate Planning for Dementia

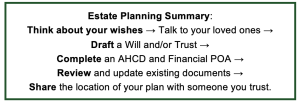

In Triage Health's free Quick Guide to Estate Planning for Alzheimer’s & Dementia Disorders, you'll learn what estate planning is, some key questions to ask yourself, and the five steps to creating an estate plan: 1. Define Your Estate, 2. Are you Responsible for Others?, 3. Which Planning Documents Do You Need, 4. Funeral & Burial Planning, 5. Review, and much more.

What is Estate Planning?

If you or a loved one have been diagnosed with dementia, you may feel overwhelmed or uncertain about how to plan for the future. Estate planning can be a very helpful step to provide peace of mind and ensure that you, your family, or your loved ones will be well taken care of in the future.

Thinking ahead about your wishes related to your health and finances can be very beneficial for your future and for those around you. If you have dementia, documenting your wishes early will allow you to be involved in decisions for your property, financial arrangements, and health care. Since symptoms of dementia worsen over time, early estate planning allows you to make decisions while you have legal capacity to do so or designate the right people to do so for you.

Most people think that you only need to plan your estate if you have a lot of money or property. But really, every adult over the age of 18 should have an estate plan. Although it can be difficult to think about your mortality, creating an estate plan allows you to express your deeply held values and personal preferences. Thinking about these decisions and preparing in advance can provide you with the peace of mind that your loved ones will know your wishes.

The following situation shows how estate planning may be helpful for persons diagnosed with dementia:

- Jane is 67 years old. She has been diagnosed with dementia.

- Jane has a spouse, children, and grandchildren who she would like to support financially. She would also like to leave her property to them when she passes.

- Jane lives alone, but she will likely require help in the future. She is experiencing memory loss, such as forgetting important dates and misplacing household items.

- Jane is her granddaughter’s primary caretaker during the weekdays.

- Jane’s rent is due soon, but she does not recall whether she has already paid the bill.

- Some of Jane’s children think that an assisted living facility, might be a good option for their mother. Others think that Jane is fine and can continue to live on her own and care for her granddaughter.

- Today, Jane is heading out to meet up with some ladies for their weekly Saturday morning tea.

- Jane cannot remember where she left her car keys. She decided to walk to her friend’s house, but unfortunately, she tripped and fell and hit her head and lost consciousness.

- One of Jane’s neighbors saw her and called 911. An ambulance took her to the hospital. The doctors are not sure if she will need surgery, but they will need her health care information.

This Guide will help explain how estate planning could help Jane:

- A will and trust could help Jane formalize her legal requests for her property when she passes.

- A limited power of attorney for Jane’s adult children could allow them to help in paying bills, monitoring her finances, and stepping in when needed.

- A health care directive would allow medical professionals to treat Jane according to her wishes and communicate with her family regarding Jane’s health.

Finally, estate planning can be empowering to persons affected by dementia as it can allow them to make independent decisions now about the future of their lives, their finances, and their health care.

Key Estate Planning Questions

- When I die…

- What do I want to happen to the property or things that I own?

- Who do I want to take care of my minor children?

- Is there someone else I want to help take care of?

- Do I have thoughts about a funeral and burial?

- If I’m unable to make my own decisions…

- Who do I want making medical decisions for me?

- Who do I want making financial decisions for me?

Steps to Create an Estate Plan

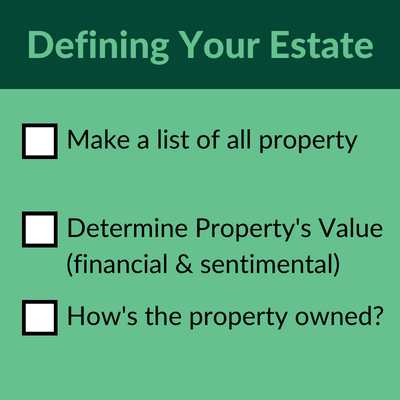

Step One: Define Your “Estate?”

Step One: Define Your “Estate?”

Your “estate” includes all the property you own at the time of your death. For example, your estate might include your home, other real estate, cars, furniture, jewelry, art, bank accounts, stocks, bonds, securities, pensions, and Social Security benefits. Even payments owed to you, like a tax refund or an inheritance, are included in your estate. Digital property like online bank accounts, electronic devices, files and photos on those devices, email and social media accounts, and blogs are also considered part of your estate. Property may also be in a safety deposit box or a storage unit so also consider personal property that may not be in the home. Depending on your state, community property laws may be applicable. It also makes sense for partners and spouses to create estate plans together to set forth joint intentions regarding shared personal property.

Once you have determined what property is included in your estate, you can determine what it is worth. To figure out the financial value of your property you can have it professionally appraised. But you should also consider if the property holds any sentimental value. For example, you may have a piano that isn’t worth a lot of money, but it has been in your family for many generations. On the other hand, if no one in your family wants the piano, maybe you will decide to donate it to a local school. Gathering this information may help you decide how to distribute things.

The final step in defining your estate is to determine how the property is owned. There is more than one way to own property. These are the three most common ways to own property:

- Individual Ownership: property you own and no one else has a legal claim to. For example, if Jim buys a car and only his name is on the title, then he owns that car alone. So, he can decide who to give his car to.

- Joint Ownership: there are two ways that you can own property with at least one other person (jointly):

- Joint Tenancy with Right of Survivorship: With this type of ownership, all of the owners hold an equal right to the property and do not need the other owner’s permission to access or use that property. For example, if Emma and Ellen own a bank account in joint tenancy with right of survivorship, each one could spend money from that account without the other’s permission. If Emma were to die, Ellen would become the sole owner of the entire account. The account would no longer be part of Emma’s estate.

- Tenancy in Common: With this type of joint ownership, each individual “tenant in common” owns a specific percentage of the property. Owners are free to withdraw/mortgage/sell only his or her own portion of that property. When a tenant in common dies, his or her share of the property would pass to his or her beneficiaries, not to the surviving tenants in common. For example, Paige and Dean own an apartment building with four units as tenants in common, with each of them owning 50% of the building. When Dean dies, ownership of two of the units would transfer to Dean’s niece, as named in Dean’s will. Now Paige and Dean’s niece own the apartment building as tenants in common.

- By Contract: Ownership of some types of property is determined by a contract (e.g., life insurance, retirement accounts). An owner has full control over the property while alive, but after death, the property transfers to a person (beneficiary) chosen by the owner. For example, Caroline has a retirement account and she named Jane as the only beneficiary. While Caroline is alive, she has the right to withdraw or add funds to that account, or even change the beneficiary. But after her death, the funds in the retirement account will go directly to Jane.

If Jane has certain assets, such as a bank account, a painting, or real estate, she may want to decide how to distribute these assets. Jane’s memory loss may get worse over time, so it is important for her to keep a detailed record of all her assets. That way, Jane can have a say over who receives the assets upon her death. Some financial accounts permit a second person to monitor an account without taking control over the finances, which may bring peace of mind without relinquishing control.

Step Two: Are You Responsible For Others?

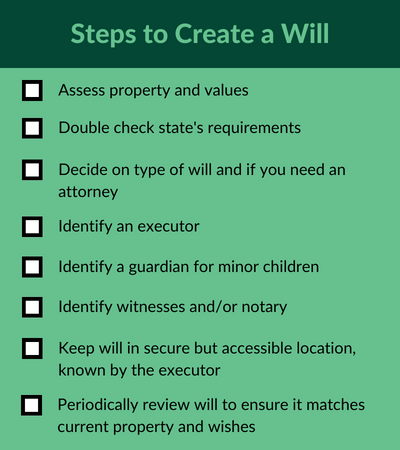

During the process of planning your estate, you should consider who you are responsible for (e.g., minor children, adult children with developmental disabilities) and how to care for them if you were no longer able to do so. If you have minor children, you may want to name one or more people to act as their legal guardians if you pass away. You should consider who you would want to manage any financial assets for those children. You can also think about any other family members and/or friends that you would like to have benefit from your assets.

Since Jane is the primary caretaker for her granddaughter, she will want to name someone specific whom she trusts to take care of her granddaughter if she is no longer able to do so herself. As her granddaughter gets older, Jane’s role may need to change depending on the level of care each of them needs.

Step Three: Which Estate Planning Documents Do You Need?

There are different documents that you should consider completing as part of your estate plan. Estate planning rules are different in each state. More information can be found by visiting TriageHealth.org/Estate-Planning.

For those with dementia, it is important to note that there is a mental capacity requirement when making the will or trust. Someone with a dementia diagnosis may lose mental capacity over time. For example, it may become difficult for him to identify his close relationships. Symptoms may vary based on the day, and some will experience “good days” and “bad days.” Capacity is satisfied as long as the individual understands the consequences of his or her actions and is able to make rational decisions.

If you are consulting a lawyer, keep in mind that they may wish consult other individuals or seek the appointment of a guardian ad litem, conservator, or guardian. Lawyers will not prepare a will or trust if they believe you lack capacity.

Jane was only recently diagnosed with dementia and has minor symptoms. She is still able to articulate the possessions she has and the people who are important in her life. However, if her symptoms worsen, she may not legally be able to make decisions about her finances because of her cognitive difficulties. Documenting Jane’s assets will make it easier for those helping her to ensure that all her assets are distributed according to her wishes.

Decisions About Your Property

The two main estate planning documents to use to describe what you want to happen with your property are a will and a trust.

1. Wills

A will is a legal document that provides instructions for what an individual would like to have happen to their property upon death. A will is also a place where parents can name a guardian for any minor children or adult children with developmental disabilities. Each state has different rules about how to create a valid will, so it is critical to check the rules in your state. There are different types of wills:

- Written: Most states require that: 1) your will be in writing; 2) you be of “sound mind;” 3) you sign the will; and 4) it be witnessed by an “uninterested party.” Some states may require two witnesses, that the witnesses are present when you sign the will, or that they will be notarized. “Sound mind” generally means that you have an understanding of what you are doing. An “uninterested party” generally means someone who is not getting anything in the will.

- Statutory: Some states (California, Maine, Michigan, New Mexico, and Wisconsin) have a statutory will form, which can be filled in with the details of your estate plan and your wishes. Will forms are free and you don’t have to hire an attorney. But they can’t be customized, so they are better for simpler estates.

- Oral: Generally, oral wills are only allowed in very limited and unusual circumstances (e.g., statements made on one’s deathbed).

There are several do-it-yourself will options if you have a relatively simple estate or cannot afford an attorney. There are online services, books, and computer software that can cost anywhere between $35-$200. You may also want to consider hiring an estate planning attorney, especially if you have a complicated estate. When an attorney helps you create a will, you will typically be charged a flat fee or an hourly rate. How much it will cost depends on factors such as the size of your estate or how complicated your wishes are. There are legal aid organizations that provide free or low-cost legal services for people with low- and moderate-income levels. For legal resources in your state, visit TriageHealth.org/State-Resources.

When you write a will, you should also consider who you want to be the executor of your will. This is the person who will ensure that your property is distributed according to your will.

You can change or revoke (cancel) your will at any time, as long as you are of sound mind. A codicil is a legal document that you can use to make changes to your will, and can be used for minor changes (e.g., adding a particular gift or updating the legal name of one of your beneficiaries after they get married). Codicils must be executed in the same way that wills are in your state. For example, if a state requires that a will be signed by two witnesses, the codicil must also be signed by two witnesses. If you need to make more substantial changes (e.g., completely removing a beneficiary or adding a new child as a beneficiary) you may want to consider revoking (cancelling) your current will and writing a new one. Generally, if you create a new will, you should destroy any older versions to avoid any confusion or doubt.

Jane has promised her property to certain people when she passes away. For example, she promised to pass down her engagement ring to her son as a family heirloom. A will helps ensure that this desire is clearly expressed and carried out, so long as the requirements for creating a valid will are met. If Jane delays too long in creating a will, she may not legally be able to make decisions about her property because of her cognitive difficulties

2. Trusts

A trust is a document that allows you to hold assets for one or more beneficiaries. A beneficiary is a person who receives the benefit of the assets in the trust. You can choose a “trustee” to oversee the assets in the trust, or you can act as your own trustee during your lifetime.

Property that can be placed in a trust includes real estate, cars, bank accounts, stocks, art, and jewelry. When you place property into a trust, legal ownership is transferred from you to the trust itself. Then the trustee has a legal responsibility to manage the property in the trust the way that you specified in the trust document. The most common types of trusts are:

Living trust: created while you are alive and is revocable until your death. Typically, you act as your own trustee, and while you are alive, you can make any changes for any reason. These may be a useful tool if you have dementia because it allows you to appoint a trustee to manage and distribute your assets if you are no longer able to do so yourself.

Testamentary trust: used to provide for individuals who need help managing their assets. Testamentary trusts can be especially useful to parents who have young children and want to provide for future education, health care, or general support. They may also be helpful in meeting ongoing expenses for dependent adults with special needs while safeguarding their government benefits (e.g., Medicaid).

Irrevocable trust: cannot be changed or revoked once created but may provide some tax benefits and protection from legal action or creditors.

Special needs trust: can be used to meet the needs of an individual with a disability. The advantage of these trusts is that the assets in the trust are not considered “countable assets” for purposes of qualification for certain governmental benefits (e.g., Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Medicaid).

If you are considering creating a trust, you should consult an estate planning attorney who is experienced in your state’s trust and tax laws to ensure that your trust is set up properly.

Jane wants to pass down some other assets, but those assets require maintenance, such as a car or investments. She also wants to give some money to her grandchildren, but only when they turn 25 years old. Jane can appoint someone, a trustee, to carry out these wishes on her behalf if she is unable to do so herself. The trustee is responsible for her investments and car and is also responsible for distributing money to Jane’s grandchildren when they turn 25 years old.

Decisions About Your Finances

3. Powers of Attorney for Financial Affairs

There may be a time when you become unable to make financial decisions for yourself and you may need help. A Power of Attorney for Financial Affairs is a legal document where you can authorize a trusted adult to make financial decisions for you. Those decisions could be as simple as depositing or withdrawing funds from a bank account, or handling other personal matters, such as receiving mail or making travel arrangements.

A springing Power of Attorney for Financial Affairs “springs” into effect only if a triggering event occurs, such as if you become incapacitated. A durable Power of Attorney for Financial Affairs takes effect when you sign it and stays in effect even if you become incapacitated in the future, but it ends when you pass away. That is when your will takes over. The person you name will be granted power to make financial decisions on your behalf.

Jane’s dementia symptoms may worsen. She needs someone to handle her financial matters, such as making sure her rent is paid on time. At some point, she may need help with other daily tasks, such as navigating her neighborhood or fixing meals. Delegating someone to make decisions for her by giving them Power of Attorney for Financial Affairs can be helpful.

A durable Power of Attorney for Health Care gives instructions about the type of health care you want and lets someone else make decisions about your health care, such as whether to accept certain forms of medical treatment and weighing courses of action based on your stated wishes.

If Jane appoints someone to be a Power of Attorney for Health Care, that person would be able to help Jane or make decisions on Jane’s behalf. In the situation where Jane suffered a fall, this person could decide whether she should risk undergoing surgery or take an alternative treatment. They could keep track of what treatments Jane has received and decide, based on her stated wishes, what course of action is most appropriate moving forward.

Decisions About Your Health Care

4. Advance Health Care Directive

There may come a time when you can no longer express your wishes about your medical care. An advance health care directive is a legal document in which you can share your preferences and provide written instructions about your medical care if you become unable to communicate. You can make decisions about whether or not you want to stop medical treatment at a future time when treatment may not be useful (e.g., stopping chemotherapy once it stops working). However, they can also be used to ensure the start or continuation of treatment at a future time when you may not be able to verbalize your consent (e.g., starting artificial hydration). As mentioned above, you can also appoint a trusted adult to make medical decisions for you in the event you are unable to communicate. For the advance health care directive forms in your state, visit TriageHealth.org/Estate-Planning.

If you anticipate requiring around-the-clock care or have specific needs that require greater attention, you may want to consider long-term care planning. You may want to plan for matters like where you will live, what services are available there, the cost of care, and what transitions will need to be made.

When making decisions about end-of-life care, there are also other resources. The POLST (Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment) Paradigm, encourages patients to talk with their health care providers about the kind of care they want. After talking, they document those decisions in a POLST form, which can be used by emergency health care providers if patients are unable to speak for themselves. Depending on the state that you live in, a POLST form might be called by another name. For more information, visit POLST.org.

In the situation where Jane suffered a fall because she was unconscious and not able to make health care decision for herself, if she had an Advance Health Care Directive, her health care team could have relied on any decisions or preferences for medical care that Jane had included in that document.

Step Four: Funeral & Burial Planning

While it can be hard to think about these issues, you may want to consider making your funeral arrangements in advance, so that your loved ones won’t have to make those decisions during a difficult time. These arrangements can also be expensive, so you should also consider how to cover these costs. Here are some things to think about:

- Where and how do I want to be laid to rest (burial, cremation, burial at sea, etc.)? Do my loved ones have any preferences?

- Do I need to buy funeral insurance to help pay for these expenses in the future?

- Do I want a memorial service, a wake, or some other type of celebration of my life?

- Who do I want my family to notify upon my passing?

For more information about funeral planning, visit: TriageHealth.org/Estate-Planning.

Jane wishes to be buried beside her spouse and parents. She does not want an elaborate memorial service and would like it to be limited to only close family and friends. She has already prepaid for certain funeral expenses. Sharing that information with her family can help them fulfill her wishes.

Step Five: Review Your Estate Plan

Occasionally, you should review your estate plan and make any needed changes, if there have been changes to your property, family, or wishes. Also, if you have moved to another state, you may also want to have a lawyer in the state where you now live review your estate plan to make sure that it complies with state laws.

Practical Tips for Estate Planning

Once you have completed your estate planning documents, you should keep them in a safe, but accessible location. Make sure that your executor, trustee, or a trusted loved one knows about the existence and location of the documents and has access to them. For example, it can cause a problem if the only copy of your will is in a safe deposit box that only you can access.

State-specific Information & Forms

For more information about planning ahead, visit TriageHealth.org/Estate-Planning. For help getting organized, visit TriageHealth.org/Quick-Guides/Checklist-GettingOrganized.

Learn More

For more information about planning ahead and other estate planning documents, visit TriageHealth.org/Estate-Planning & our Cancer Finances Estate Planning Module. For help getting organized, download our Checklist: Getting Organized.

Sharing Our Quick Guides

We're glad you found this resource helpful! Please feel free to share this resource with your communities or to post a link on your organization's website. If you are a health care professional, we provide free, bulk copies of many of our resources. To make a request, visit TriageHealth.org/MaterialRequest.

However, this content may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without the express permission of Triage Cancer. Please email us at TriageHealth@TriageCancer.org to request permission.

Last reviewed for updates: 01/2022

Disclaimer: This handout is intended to provide general information on the topics presented. It is provided with the understanding that Triage Cancer is not engaged in rendering any legal, medical, or professional services by its publication or distribution. Although this content was reviewed by a professional, it should not be used as a substitute for professional services. © Triage Cancer 2023